Recently in clinic, I had a 12-year-old patient, Jade (not real name), brought in by her mom. Jade came for an appointment about a physical health problem, but when I asked about school, I learned she had missed over 20 days of it since the beginning of the school year. Jade told me she just felt nervous at school and didn’t like it. She said she felt “anxious,” but she had difficulty describing her anxiety. She told me that she had no friends (and no one was being mean to her). She was currently in 7th grade, and 6th grade had been online.

Like Jade, many youth find the return to in-person school challenging, and a major reason is their anxiety.

School refusal has been going up for years. One suspected reason, of many, is that youth now have screens that they use all day to cope when home from school —TV never provided this much of a pull. We know that this year as in-person school returned, school refusal went up.

I use the term school refusal to include going to school late, missing individual classes, and missing entire school days. School refusal can be related to many things, but today I am focusing on anxiety and tips on how to help.

Anxiety sensitivity is a phenomenon where a person's fear of bodily sensations is related to anxiety. The person is convinced that sensations like a stomach ache, for example, are harmful. They can start to get more and more anxious about the bodily sensation, worrying about things like, “What if it causes me to do something embarrassing like vomiting at school?”

When a child calls to get picked up for various complaints such as headaches or nausea that are ongoing and may have an anxiety component, and we do it, the child is internalizing the idea that they should not feel the sensation.

For sure, we can pick them up at times, but they need to get the message that it is okay to feel these things and that they can get through the sensations. Like emotions, the feelings in their bodies will pass too.

Another problem of picking up our child from school in these situations is that this act of “rescuing” them then reinforces the behavior of calling to be picked up because the reward of getting relief from any bodily sensations is so powerful.

As a parent, not coming to pick up our children when they are not feeling well is counter to every bone in our body. Knowing when to come and pick them up and when it may be in their best interest to stay at school takes help. So, having communication with teachers, counselors, school nurses, etc., is incredibly important.

All of us who have experienced this, and have learned how to gauge the situation to determine when to rescue our child versus not, can help other parents facing this difficulty.

Learn more about showing our movies in your school or community!

Join Screenagers filmmaker Delaney Ruston MD for our latest Podcast

Learn more about our Screen-Free Sleep campaign at the website!

Our movie made for parents and educators of younger kids

Learn more about showing our movies in your school or community!

Our society trains us that family matters are private. Really? Always? I believe we are better off as a society when we allow ourselves to be vulnerable by trying to help. For instance, let’s say a dad heard that their son’s friend is missing a lot of days of school, and it may be coming from anxiety. The dad has dealt with this in his family and decides to reach out to this boy's dad. Perhaps, he emails something like,

“Hi, I have heard that Fred has not been at school much. I am not exactly sure why but I just wanted to say that one of our kids has missed a lot of school due to anxiety and if that is at all at play, I would be happy to share what we’ve been learning through all this. Even if that is not what is happening with Fred, please know I am here to talk at any time. Here is my cell.”

Let’s make sure our teens know that anxiety gets housed in a part of the brain called the amygdala (an almond-shaped collection of neurons in the right and left hemispheres of the brain). It might be useful for your teen to know that when they help a friend get through a flood of anxious feelings, they are aiding that friend in retraining their amygdala. (This is another link on the Screenagers Movie website where you can learn more about anxiety.)

Helping the friend get some “self distancing” can be very effective. Saying things like, “That is just the stress area of your brain going on a sprint. I am here with you, and this sprint will end. Let's count to 10 together.”

Another thing your teen can offer is to do a cold water face plunge/splash with their anxious friend. The cold water causes the body to turn on its parasympathetic nervous system, which brings down one’s heart rate and can help them feel calmer.

Learn more about showing our movies in your school or community!

Join Screenagers filmmaker Delaney Ruston MD for our latest Podcast

Learn more about our Screen-Free Sleep campaign at the website!

Our movie made for parents and educators of younger kids

Join Screenagers filmmaker Delaney Ruston MD for our latest Podcast

Jade’s mom told me about her own mental health problems, including recovering from alcoholism. She didn’t want Jade to miss so much school, but whenever Jade pushed hard against going to school, her mom gave in. She also let Jade be on her phone all day (Jade was not at a hybrid school, so she was not using her phone for classes). Jade had a caseworker and counselor, but Jade and her mom were not in regular contact with them.

The good news was that as we started to talk about changes her mom could do to help Jade attend school, she was receptive to getting advice.

We did the following work together:

I will be following up with Jade and her mom. I know this will not be a quick fix and that the key is helping to get them continued support and resources. I shared their story to remind you that healthcare providers can be a place to turn if anxiety is causing distress and comprising healthy development.

As we’re about to celebrate 10 years of Screenagers, we want to hear what’s been most helpful and what you’d like to see next.

Please click here to share your thoughts with us in our community survey. It only takes 5–10 minutes, and everyone who completes it will be entered to win one of five $50 Amazon vouchers.

Recently in clinic, I had a 12-year-old patient, Jade (not real name), brought in by her mom. Jade came for an appointment about a physical health problem, but when I asked about school, I learned she had missed over 20 days of it since the beginning of the school year. Jade told me she just felt nervous at school and didn’t like it. She said she felt “anxious,” but she had difficulty describing her anxiety. She told me that she had no friends (and no one was being mean to her). She was currently in 7th grade, and 6th grade had been online.

Like Jade, many youth find the return to in-person school challenging, and a major reason is their anxiety.

School refusal has been going up for years. One suspected reason, of many, is that youth now have screens that they use all day to cope when home from school —TV never provided this much of a pull. We know that this year as in-person school returned, school refusal went up.

I use the term school refusal to include going to school late, missing individual classes, and missing entire school days. School refusal can be related to many things, but today I am focusing on anxiety and tips on how to help.

Anxiety sensitivity is a phenomenon where a person's fear of bodily sensations is related to anxiety. The person is convinced that sensations like a stomach ache, for example, are harmful. They can start to get more and more anxious about the bodily sensation, worrying about things like, “What if it causes me to do something embarrassing like vomiting at school?”

When a child calls to get picked up for various complaints such as headaches or nausea that are ongoing and may have an anxiety component, and we do it, the child is internalizing the idea that they should not feel the sensation.

For sure, we can pick them up at times, but they need to get the message that it is okay to feel these things and that they can get through the sensations. Like emotions, the feelings in their bodies will pass too.

Another problem of picking up our child from school in these situations is that this act of “rescuing” them then reinforces the behavior of calling to be picked up because the reward of getting relief from any bodily sensations is so powerful.

As a parent, not coming to pick up our children when they are not feeling well is counter to every bone in our body. Knowing when to come and pick them up and when it may be in their best interest to stay at school takes help. So, having communication with teachers, counselors, school nurses, etc., is incredibly important.

All of us who have experienced this, and have learned how to gauge the situation to determine when to rescue our child versus not, can help other parents facing this difficulty.

Our society trains us that family matters are private. Really? Always? I believe we are better off as a society when we allow ourselves to be vulnerable by trying to help. For instance, let’s say a dad heard that their son’s friend is missing a lot of days of school, and it may be coming from anxiety. The dad has dealt with this in his family and decides to reach out to this boy's dad. Perhaps, he emails something like,

“Hi, I have heard that Fred has not been at school much. I am not exactly sure why but I just wanted to say that one of our kids has missed a lot of school due to anxiety and if that is at all at play, I would be happy to share what we’ve been learning through all this. Even if that is not what is happening with Fred, please know I am here to talk at any time. Here is my cell.”

Let’s make sure our teens know that anxiety gets housed in a part of the brain called the amygdala (an almond-shaped collection of neurons in the right and left hemispheres of the brain). It might be useful for your teen to know that when they help a friend get through a flood of anxious feelings, they are aiding that friend in retraining their amygdala. (This is another link on the Screenagers Movie website where you can learn more about anxiety.)

Helping the friend get some “self distancing” can be very effective. Saying things like, “That is just the stress area of your brain going on a sprint. I am here with you, and this sprint will end. Let's count to 10 together.”

Another thing your teen can offer is to do a cold water face plunge/splash with their anxious friend. The cold water causes the body to turn on its parasympathetic nervous system, which brings down one’s heart rate and can help them feel calmer.

Jade’s mom told me about her own mental health problems, including recovering from alcoholism. She didn’t want Jade to miss so much school, but whenever Jade pushed hard against going to school, her mom gave in. She also let Jade be on her phone all day (Jade was not at a hybrid school, so she was not using her phone for classes). Jade had a caseworker and counselor, but Jade and her mom were not in regular contact with them.

The good news was that as we started to talk about changes her mom could do to help Jade attend school, she was receptive to getting advice.

We did the following work together:

I will be following up with Jade and her mom. I know this will not be a quick fix and that the key is helping to get them continued support and resources. I shared their story to remind you that healthcare providers can be a place to turn if anxiety is causing distress and comprising healthy development.

Sign up here to receive the weekly Tech Talk Tuesdays newsletter from Screenagers filmmaker Delaney Ruston MD.

We respect your privacy.

Recently in clinic, I had a 12-year-old patient, Jade (not real name), brought in by her mom. Jade came for an appointment about a physical health problem, but when I asked about school, I learned she had missed over 20 days of it since the beginning of the school year. Jade told me she just felt nervous at school and didn’t like it. She said she felt “anxious,” but she had difficulty describing her anxiety. She told me that she had no friends (and no one was being mean to her). She was currently in 7th grade, and 6th grade had been online.

Like Jade, many youth find the return to in-person school challenging, and a major reason is their anxiety.

School refusal has been going up for years. One suspected reason, of many, is that youth now have screens that they use all day to cope when home from school —TV never provided this much of a pull. We know that this year as in-person school returned, school refusal went up.

I use the term school refusal to include going to school late, missing individual classes, and missing entire school days. School refusal can be related to many things, but today I am focusing on anxiety and tips on how to help.

Anxiety sensitivity is a phenomenon where a person's fear of bodily sensations is related to anxiety. The person is convinced that sensations like a stomach ache, for example, are harmful. They can start to get more and more anxious about the bodily sensation, worrying about things like, “What if it causes me to do something embarrassing like vomiting at school?”

When a child calls to get picked up for various complaints such as headaches or nausea that are ongoing and may have an anxiety component, and we do it, the child is internalizing the idea that they should not feel the sensation.

For sure, we can pick them up at times, but they need to get the message that it is okay to feel these things and that they can get through the sensations. Like emotions, the feelings in their bodies will pass too.

Another problem of picking up our child from school in these situations is that this act of “rescuing” them then reinforces the behavior of calling to be picked up because the reward of getting relief from any bodily sensations is so powerful.

As a parent, not coming to pick up our children when they are not feeling well is counter to every bone in our body. Knowing when to come and pick them up and when it may be in their best interest to stay at school takes help. So, having communication with teachers, counselors, school nurses, etc., is incredibly important.

All of us who have experienced this, and have learned how to gauge the situation to determine when to rescue our child versus not, can help other parents facing this difficulty.

Catherine Price’s “Rebel's Code” focuses on intentional technology use and prioritizing real-world friendship, freedom, and fun. Her book The Amazing Generation, co-written with Jonathan Haidt, introduces these concepts to children through interactive formats and teen perspectives. Research indicates that when adolescents understand how platforms are designed to exploit attention, they show greater motivation to limit their social media use.

READ MORE >

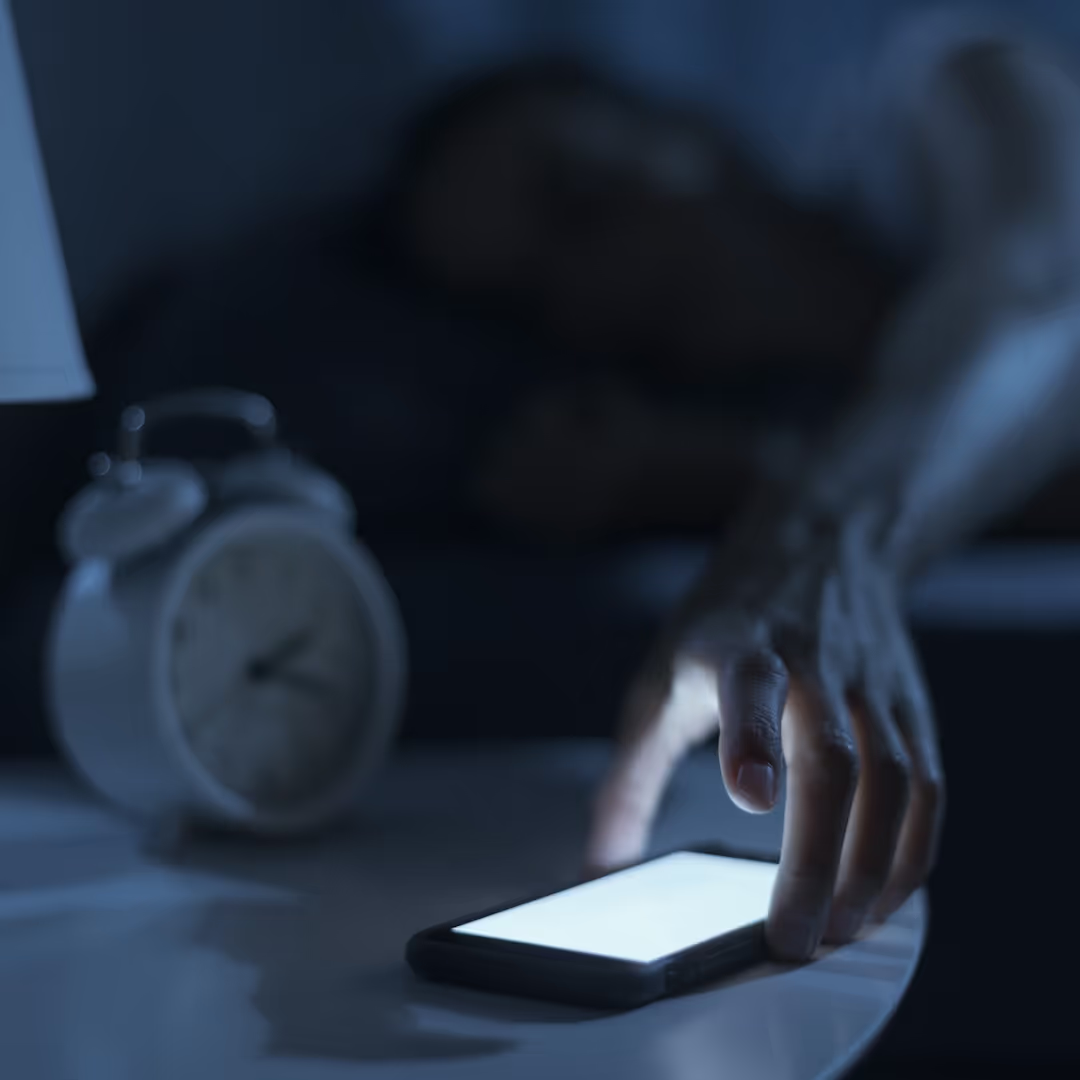

Many adults keep their phones by the bed — it feels harmless, even necessary. But what if that habit is quietly affecting our sleep and the example we set for our kids? In this week’s blog, Dr. Ruston shares two key things every parent should know about sleeping next to a phone, and how small nighttime tech changes can make a big difference for the whole family.

READ MORE >for more like this, DR. DELANEY RUSTON'S NEW BOOK, PARENTING IN THE SCREEN AGE, IS THE DEFINITIVE GUIDE FOR TODAY’S PARENTS. WITH INSIGHTS ON SCREEN TIME FROM RESEARCHERS, INPUT FROM KIDS & TEENS, THIS BOOK IS PACKED WITH SOLUTIONS FOR HOW TO START AND SUSTAIN PRODUCTIVE FAMILY TALKS ABOUT TECHNOLOGY AND IT’S IMPACT ON OUR MENTAL WELLBEING.